PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A Brown University-led research team has for the first time discovered evidence of water that came from deep within the Moon, a revelation that strongly suggests water has been a part of the Moon since its early existence – and perhaps ever since it was created by a cataclysmic collision between the early Earth and a Mars-sized object about 4.5 billion years ago.

In a paper published in the July 10 issue of the journal Nature, the team, led by Alberto Saal, assistant professor of geological sciences at Brown, believes that the water was contained in magmas erupted from fire fountains onto the surface of the Moon more than 3 billion years ago. About 95 percent of the water vapor from the magma was lost to space during this eruptive “degassing,” the team estimates. But traces of water vapor may have drifted toward the cold poles of the Moon, where they may remain as ice in permanently shadowed craters.

NASA plans to send its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter later this year to search for evidence of water ice at the Moon’s south pole. If water is found, the researchers may have figured out the origin.

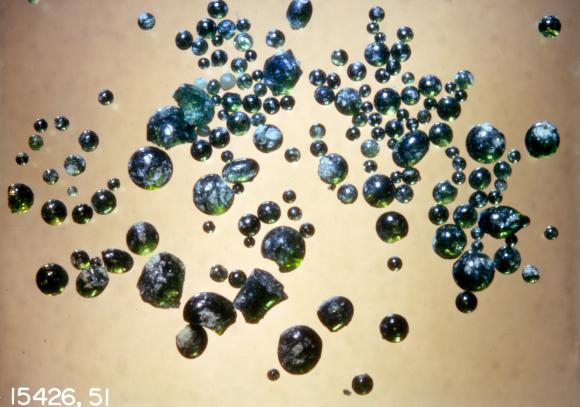

The water clue came from lunar volcanic glasses, pebble-like beads collected and returned to Earth by NASA’s Apollo missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the decades since, scientists have sought to determine the content and origin of a class of chemical elements known as volatiles in the multicolored glasses. In particular, they searched the glasses for signs of water. But such evidence had remained elusive, consistent with the general consensus that the Moon is dry.

Now, that evidence has been found.

“What is important for me is it’s telling me something about the origin of the Moon and the Earth and the presence of water at very early times,” said Saal, the paper’s lead author.

Three other researchers from the Department of Geological Sciences at Brown – professors Reid Cooper and Malcolm Rutherford, and graduate student Mauro Lo Cascio – contributed to the research. Erik Hauri from the Carnegie Institution for Science developed the analytical technique used to identify water and the other volatiles. James Van Orman from Case Western Reserve University also participated in the work.

Based on their observations that nearly all the water in the lunar magma was lost to space during the eruptions, the researchers calculated that the pre-eruption magma may have contained water up to 750 parts per million — similar to the water content of primitive magmas that erupted on the Earth’s seafloor at midocean ridges.

“This suggests the very intriguing possibility that the Moon’s interior might have contained just as much water as the Earth’s depleted upper mantle,” Hauri said.

Hauri used secondary mass ion spectrometry, a technique that measures the elemental composition of solid materials, to detect the minute amounts of water in the samples.

“We developed a way to detect as little as five parts per million of water,” Hauri said. “We were really surprised to find a whole lot more in these tiny glass beads, up to 46 parts per million.”

The team then confirmed through a series of tests that hydrogen had been present all along, and the samples had not been infused by hydrogen-rich solar winds or tainted by other volatiles.

“This confirms that water comes from deep within the mantle of the Moon,” Saal said. “It has nothing to do with secondary processes, such as contamination or solar wind.”

The research also may yield additional insight into how long water has been on Earth, Saal added.

“It suggests that water was present within the Earth before the giant collision that formed the Moon,” Saal said. “That points to two possibilities: Water either was not completely vaporized in that collision or it was added a short time – less than 100 million years – afterward by volatiles introduced from the outside, such as with meteorites.”

The researchers this summer will study volcanic glasses gathered from other Apollo missions for evidence of water.

NASA’s Cosmochemistry Program funded the research.